To Know What You Know: With Guests David Dunning & Andrew Flack

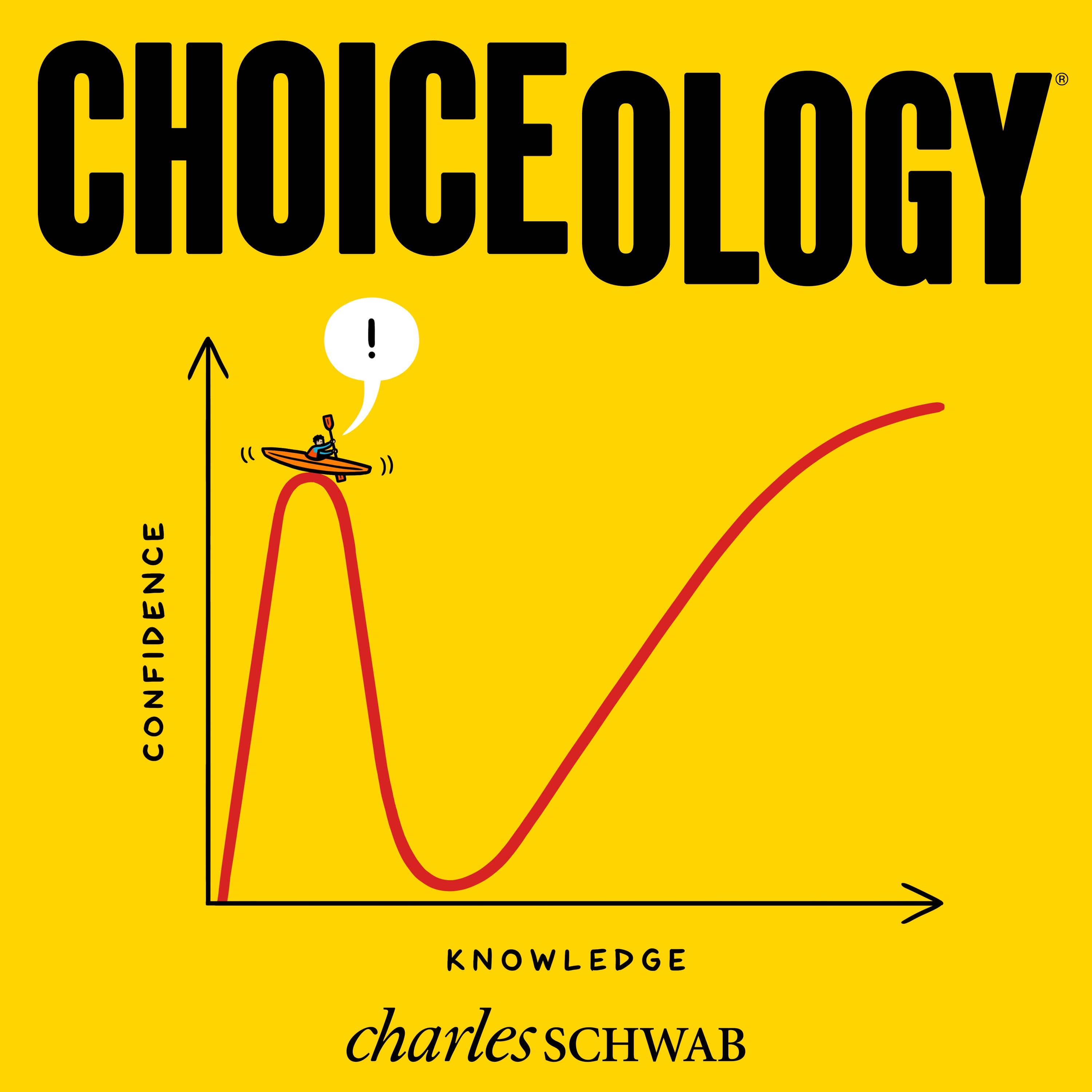

In this episode of Choiceology with Katy Milkman, we look at the often-misunderstood and surprisingly common Dunning-Kruger effect with an interview featuring one of the researchers who first identified it, David Dunning.

But we start with the story of Cecilia Jimenez, the humble Spanish grandmother and amateur landscape painter who took it upon herself to restore a fresco in her local church. The results made international headlines—and briefly made Ceclia Jimenez a household name—for all the wrong reasons.

Andrew Flack has a lot of compassion for Cecilia. He met with her several times in the process of writing an opera with composer Paul Fowler called Behold the Man about Ceclia's ill-fated but ultimately beneficial project.

Next, David Dunning explains how—contrary to popular belief—we are all at the mercy of the Dunning-Kruger effect from time to time, and that we should be more humble in recognizing what we don't know about what we don't know.

David Dunning is the Ann and Charles R. Walgreen, Jr., Professor of the Study of Human Understanding at the University of Michigan. The paper "Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One's Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments," co-authored with Justin Kruger, led to the bias being named The Dunning-Kruger effect.

Learn more about behavioral finance.

Explore more topics

The comments, views, and opinions expressed in the presentation are those of the speakers and do not necessarily represent the views of Charles Schwab.

Data contained herein from third party providers is obtained from what are considered reliable source. However, its accuracy, completeness or reliability cannot be guaranteed and Charles Schwab & Co. expressly disclaims any liability, including incidental or consequential damages, arising from errors or omissions in this publication.

All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice in reaction to shifting market conditions.

All names and market data shown above are for illustrative purposes only and are not a recommendation, offer to sell, or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security. Supporting documentation for any claims or statistical information is available upon request.

Investing involves risk including loss of principal.

The book How to Change: The Science of Getting From Where You Are to Where You Want to Be is not affiliated with, sponsored by, or endorsed by Charles Schwab & Co., Inc. (CS&Co.). Charles Schwab & Co., Inc. (CS&Co.) has not reviewed the book and makes no representations about its content.

Apple, the Apple logo, iPad, iPhone, and Apple Podcasts are trademarks of Apple Inc., registered in the U.S. and other countries. App Store is a service mark of Apple Inc.

Spotify and the Spotify logo are registered trademarks of Spotify AB.